Reading Passage 1

Advantages of public transport

A New study conducted for the World Bank by Murdoch University’s Institute for Science and Technology Policy (ISTP) has demonstrated that public transport is more efficient than cars. The study compared the proportion of wealth poured into transport by thirty-seven cities around the world. This included both the public and private costs of building, maintaining and using a transport system.

The study found that the Western Australian city of Perth is a good example of a city with minimal public transport. As a result, 17% of its wealth went into transport costs. Some European and Asian cities, on the other hand, spent as little as 5%. Professor Peter Newman, ISTP Director, pointed out that these more efficient cities were able to put the difference into attracting industry and jobs or creating a better place to live.

According to Professor Newman, the larger Australian city of Melbourne is a rather unusual city in this sort of comparison. He describes it as two cities: ‘A European city surrounded by a car-dependent one’. Melbourne’s large tram network has made car use in the inner city much lower, but the outer suburbs have the same car-based structure as most other Australian cities. The explosion in demand for accommodation in the inner suburbs of Melbourne suggests a recent change in many people’s preferences as to where they live.

Newman says this is a new, broader way of considering public transport issues. In the past, the case for public transport has been made on the basis of environmental and social justice considerations rather than economics. Newman, however, believes the study demonstrates that ‘the auto-dependent city model is inefficient and grossly inadequate in economic as well as environmental terms’.

Bicycle use was not included in the study but Newman noted that the two most ‘bicycle friendly’ cities considered – Amsterdam and Copenhagen – were very efficient, even though their public transport systems were ‘reasonable but not special’.

It is common for supporters of road networks to reject the models of cities with good public transport by arguing that such systems would not work in their particular city. One objection is climate. Some people say their city could not make more use of public transport because it is either too hot or too cold. Newman rejects this, pointing out that public transport has been successful in both Toronto and Singapore and, in fact, he has checked the use of cars against climate and found ‘zero correlation’.

When it comes to other physical features, road lobbies are on stronger ground. For example, Newman accepts it would be hard for a city as hilly as Auckland to develop a really good rail network. However, he points out that both Hong Kong and Zürich have managed to make a success of their rail systems, heavy and light respectively, though there are few cities in the world as hilly.

- In fact, Newman believes the main reason for adopting one sort of transport over another is politics: ‘The more democratic the process, the more public transport is favored.’ He considers Portland, Oregon, a perfect example of this. Some years ago, federal money was granted to build a new road. However, local pressure groups forced a referendum over whether to spend the money on light rail instead. The rail proposal won and the railway worked spectacularly well. In the years that have followed, more and more rail systems have been put in, dramatically changing the nature of the city. Newman notes that Portland has about the same population as Perth and had a similar population density at the time.

- In the UK, travel times to work had been stable for at least six centuries, with people avoiding situations that required them to spend more than half an hour travelling to work. Trains and cars initially allowed people to live at greater distances without taking longer to reach their destination. However, public infrastructure did not keep pace with urban sprawl, causing massive congestion problems which now make commuting times far higher.

- There is a widespread belief that increasing wealth encourages people to live farther out where cars are the only viable transport. The example of European cities refutes that. They are often wealthier than their American counterparts but have not generated the same level of car use. In Stockholm, car use has actually fallen in recent years as the city has become larger and wealthier. A new study makes this point even more starkly. Developing cities in Asia, such as Jakarta and Bangkok, make more use of the car than wealthy Asian cities such as Tokyo and Singapore. In cities that developed later, the World Bank and Asian Development Bank discouraged the building of public transport and people have been forced to rely on cars – creating the massive traffic jams that characterize those cities.

- Newman believes one of the best studies on how cities built for cars might be converted to rail use is The Urban Village report, which used Melbourne as an example. It found that pushing everyone into the city centre was not the best approach. Instead, the proposal advocated the creation of urban villages at hundreds of sites, mostly around railway stations.

- It was once assumed that improvements in telecommunications would lead to more dispersal in the population as people were no longer forced into cities. However, the ISTP team’s research demonstrates that the population and job density of cities rose or remained constant in the 1980s after decades of decline. The explanation for this seems to be that it is valuable to place people working in related fields together. ‘The new world will largely depend on human creativity, and creativity flourishes where people come together face-to-face.’

Questions 1-5

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1-13, which are based on Reading Passage 1.

Reading Passage 1 has five paragraphs, A-E.

Choose the correct heading for each paragraph from the list of headings below.

Write the correct number i-viii, in boxes 1-5 on your answer sheet.

List of Headings

- Avoiding an overcrowded centre

- successful exercise in people power

- The benefits of working together in cities

- Higher incomes need not mean more cars

- Economic arguments fail to persuade

- The impact of telecommunications on population distribution

- Increases in travelling time

- Responding to arguments against public transport.

- Paragraph A

- Paragraph B

- Paragraph C

- Paragraph D

- Paragraph E

Questions 6-10

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 95?

In boxes 6-10 on your answer sheet, write

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

- The ISTP study examined public and private systems in every city in the world.

- Efficient cities can improve the quality of life for their inhabitants.

- An inner-city tram network is dangerous for car drivers.

- In Melbourne, people prefer to live in the outer suburbs.

- Cities with high levels of bicycle usage can be efficient even when public transport is only averagely good.

Questions 11-13

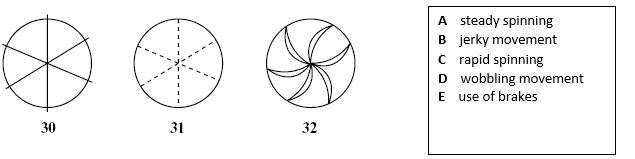

Look at the following cities (Questions 11-13) and the list of descriptions below.

Match each city with the correct description, A-F.

Write the correct letter, A-F, in boxes 11-13 on your answer sheet.

List of Descriptions

- successfully uses a light rail transport system in hilly environment

- successful public transport system despite cold winters

- profitably moved from road to light rail transport system

- hilly and inappropriate for rail transport system

- heavily dependent on cars despite widespread poverty

- inefficient due to a limited public transport system

Reading Passage 2

Greying Population Stays in the Pink

Elderly people are growing healthier, happier and more independent, say American scientists. The results of a 14-year study to be announced later this month reveal that the diseases associated with old age are afflicting fewer and fewer people and when they do strike, it is much later in life.

In the last 14 years, the National Long-term Health Care Survey has gathered data on the health and lifestyles of more than 20,000 men and women over 65. Researchers, now analysing the results of data gathered in 1994, say arthritis, high blood pressure and circulation problems -the major medical complaints in this age group – are troubling a smaller proportion every year. And the data confirms that the rate at which these diseases are declining continues to accelerate. Other diseases of old age – dementia, stroke, arteriosclerosis and emphysema – are also troubling fewer and fewer people.

‘It really raises the question of what should be considered normal ageing,’ says Kenneth Manton, a demographer from Duke University in North Carolina. He says the problems doctors accepted as normal in a 65-year-old in 1982 are often not appearing until people are 70 or 75.

Clearly, certain diseases are beating a retreat in the face of medical advances. But there may be other contributing factors. Improvements in childhood nutrition in the first quarter of the twentieth century, for example, gave today’s elderly people a better start in life than their predecessors.

On the downside, the data also reveals failures in public health that have caused surges in some illnesses. An increase in some cancers and bronchitis may reflect changing smoking habits and poorer air quality, say the researchers. ‘These may be subtle influences,’ says Manton, ‘but our subjects have been exposed to worse and worse pollution for over 60 years. It’s not surprising we see some effect.’

One interesting correlation Manton uncovered is that better-educated people are likely to live longer. For example, 65-year-old women with fewer than eight years of schooling are expected, on average, to live to 82. Those who continued their education live an extra seven years. Although some of this can be attributed to a higher income, Manton believes it is mainly because educated people seek more medical attention.

The survey also assessed how independent people over 65 were, and again found a striking trend. Almost 80% of those in the 1994 survey could complete everyday activities ranging from eating and dressing unaided to complex tasks such as cooking and managing their finances. That represents a significant drop in the number of disabled old people in the population. If the trends apparent in the United States 14 years ago had continued, researchers calculate there would be an additional one million disabled elderly people in today’s population. According to Manton, slowing the trend has saved the United States government’s Medicare system more than $200 billion, suggesting that the greying of America’s population may prove less of a financial burden than expected.

The increasing self-reliance of many elderly people is probably linked to a massive increase in the use of simple home medical aids. For instance, the use of raised toilet seats has more than doubled since the start of the study, and the use of bath seats has grown by more than 50%. These developments also bring some health benefits, according to a report from the MacArthur Foundation’s research group on successful ageing. The group found that those elderly people who were able to retain a sense of independence were more likely to stay healthy in old age.

Maintaining a level of daily physical activity may help mental functioning, says Carl Cotman, a neuroscientist at the University of California at Irvine. He found that rats that exercise on a treadmill have raised levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor coursing through their brains. Cotman believes this hormone, which keeps neurons functioning, may prevent the brains of active humans from deteriorating.

As part of the same study, Teresa Seeman, a social epidemiologist at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, found a connection between self-esteem and stress in people over 70. In laboratory simulations of challenging activities such as driving, those who felt in control of their lives pumped out lower levels of stress hormones such as cortisol. Chronically high levels of these hormones have been linked to heart disease.

But independence can have drawbacks. Seeman found that elderly people who felt emotionally isolated maintained higher levels of stress hormones even when asleep. The research suggests that older people fare best when they feel independent but know they can get help when they need it.

‘Like much research into ageing, these results support common sense,’ says Seeman. They also show that we may be underestimating the impact of these simple factors. ‘The sort of thing that your grandmother always told you turns out to be right on target,’ she says.

Questions 14-22

Complete the summary using the list of words, A-Q. below.

Write the correct letter, A-Q, in boxes 14-22 on your answer sheet.

Research carried out by scientists in the United States has shown that the proportion of people over 65 suffering from the most common age-related medical problems is (14) ………………….. and that the speed of this change is (15)……………………….. It also seems that these diseases ere affecting people (16) …………………….. in life than they did in the past. This is largely due to developments in (17) ……………………. , but other factors such as improved (18) …………………… may also be playing a part. Increases in some other illnesses may be due to changes in personal habits and to (19) ………………………. The research establishes a link between levels of (20) ……………………. and life expectancy. It also shows that there has been a considerable reduction in the number of elderly people who are (21) …………………….. which means that the (22) …………………… involved in supporting this section of the population may be less than previously predicted.

- cost

- falling

- technology

- undernourished

- earlier

- later

- disabled

- more

- Increasing

- nutrition

- education

- constant

- medicine

- pollution

- environmental

- health

- independent

Questions 23-26

Complete each sentence with the correct ending, A-H, below.

Write the correct letter, A-H, in boxes 23-26 on your answer sheet.

- Home medical aids

- Regular amounts of exercise

- Feelings of control over life

- Feelings of loneliness

- may cause heart disease.

- can be helped by hormone treatment.

- may cause rises in levels of stress hormones.

- have cost the United States government more than $200 billion.

- may help prevent mental decline.

- may get stronger at night.

- allow old people to be more independent.

- can reduce stress in difficult situations.

Reading Passage 3

Numeration

One of the first great intellectual feats of a young child is learning how to talk, closely followed by learning how to count. From earliest childhood, we are so bound up with our system of numeration that it is a feat of imagination to consider the problems faced by early humans who had not yet developed this facility. Careful consideration of our system of numeration leads to the conviction that, rather than being a facility that comes naturally to a person, it is one of the great and remarkable achievements of the human race.

It is impossible to learn the sequence of events that led to our developing the concept of number. Even the earliest of tribes had a system of numeration that, if not advanced, was sufficient for the tasks that they had to perform. Our ancestors had little use for actual numbers; instead, their considerations would have been more of the kind Is this enough? rather than How many? when they were engaged in food gathering, for example. However, when early humans first began to reflect on the nature of things around them, they discovered that they needed an idea of number simply to keep their thoughts in order. As they began to settle, grow plants and herd animals, the need for a sophisticated number system became paramount. It will never be known how and when this numeration ability developed, but it is certain that numeration was well developed by the time humans had formed even semipermanent settlements.

Evidence of early stages of arithmetic and numeration can be readily found. The indigenous peoples of Tasmania were only able to count one, two, many; those of South Africa counted one, two, two and one, two twos, two twos and one, and so on. But in real situations the number and words are offen accompanied by gestures to help resolve any confusion. For example, when using the one, two, many types of system, the word many would mean, Look my hands and see how many fingers I am showing you. This basic approach is limited in the range of numbers that it can express, but this range will generally suffice when dealing with the simpler aspects of human existence.

The lack of ability of some cultures to deal with large numbers is not really surprising. European languages, when traced back to their earlier version, are very poor in number words and expressions. The ancient Gothic word for ten, tachund, is used to express the number 100 as tachund tachund. By the seventh century, the word teon had become interchangeable with the tachund or hund of the Anglo-Saxon language, and so 100 was denoted as hund teontig, or ten times ten. The average person in the seventh century in Europe was not as familiar with numbers as we are today. In fact, to qualify as a witness in a court of law a man had to be able to count to nine!

Perhaps the most fundamental step in developing a sense of number is not the ability to count, but rather to see that a number is really an abstract idea instead of a simple attachment to a group of particular objects. It must have been within the grasp of the earliest humans to conceive that four birds are distinct from two birds; however, it is not an elementary step to associate the number 4, as connected with four birds, to the number 4, as connected with four rocks. Associating a number as one of the qualities of a specific object is a great hindrance to the development of a true number sense. When the number 4 can be registered in the mind as a specific word, independent of the object being referenced, the individual is ready to take the first step toward the development of a notational system for numbers and, from there, to arithmetic.

Traces of the very first stages in the development of numeration can be seen in several living languages today. The numeration system of the Tsimshian language in British Columbia contains seven distinct sets of words for numbers according to the class of the item being counted: for counting flat objects and animals, for round objects and time, for people, for long objects and trees, for canoes, for measures, and for counting when no particular object is being enumerated. It seems that the last is a later development while the first six groups show the relics of an older system. This diversity of number names can also be found in some widely used languages such as Japanese.

Intermixed with the development of a number sense is the development of an ability to count. Counting is not directly related to the formation of a number concept because it is possible to count by matching the items being counted against a group of pebbles, grains of corn, or the counter’s fingers. These aids would have been indispensable to very early people who would have found the process impossible without some form of mechanical aid. Such aids, while different, are still used even by the most educated in today’s society due to their convenience. All counting ultimately involves reference to something other than the things being counted. At first, it may have been grains or pebbles but now it is a memorised sequence of words that happen to be the names of the numbers.

Questions 27-31

Complete each sentence with the correct ending, A-G, below.

Write the correct letter, A-G, in boxes 27-31 on your answer sheet.

A was necessary in order to fulfil a civic role.B was necessary when people began farming.C was necessary for the development of arithmetic.D persists in all societies.E was used when the range of number words was restricted.F can be traced back to early European languages.G was a characteristic of early numeration systems.

- A developed system of numbering

- An additional hand signal

- In seventh-century Europe, the ability to count to a certain number

- Thinking about numbers as concepts separate from physical objects

- Expressing number differently according to class of item

Questions 32-40

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 3?

In boxes 32-40 on your answer sheet, write:

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

- For the earliest tribes, the concept of sufficiency was more important than the concept of quantity.

- Indigenous Tasmanians used only four terms to indicate numbers of objects.

- Some peoples with simple number systems use body language to prevent misunderstanding of expressions of the number.

- All cultures have been able to express large numbers clearly.

- The word ‘thousand’ has Anglo-Saxon origins.

- In general, people in seventh-century Europe had poor counting ability.

- In the Tsimshian language, the number for long objects and canoes is expressed with the same word.

- The Tsimshian language contains both older and newer systems of counting.

- Early peoples found it easier to count by using their fingers rather than a group of pebbles.

Academic Reading Passage 1 Advantages of public transport Answers

- ii

- vii

- iv

- i

- iii

- false

- true

- not given

- false

- true

- F

- D

- C

Academic Reading Passage 2 Greying Population Stays in the Pink Answers

- falling

- increasing

- later

- medicine

- nutrition

- pollution

- education

- disabled

- cost

- G

- E

- H

- C

Academic Reading Passage 3 Numeration Answers

- B

- E

- A

- C

- G

- true

- false

- true

- false

- not given

- true

- false

- true

- not given