Reading Passage 1

Australia’s Sporting Success

- They play hard, they play often, and they play to win. Australian sports teams win more than their fair share of titles, demolishing rivals with seeming ease. How do they do it? A big part of the secret is an extensive and expensive network of sporting academies underpinned by science and medicine. At the Australian Institute of Sport (AIS), hundreds of youngsters and pros live and train under the eyes of coaches. Another body, the Australian Sports Commission (ASC), finances programmes of excellence in a total of 96 sports for thousands of sportsmen and women. Both provide intensive coaching, training facilities and nutritional advice.

- Inside the academies, science takes centre stage. The AIS employs more than 100 sports scientists and doctors, and collaborates with scores of others in universities and research centres. AIS scientists work across a number of sports, applying skills learned in one – such as building muscle strength in golfers – to others, such as swimming and squash. They are backed up by technicians who design instruments to collect data from athletes. They all focus on one aim: winning. ‘We can’t waste our time looking at ethereal scientific questions that don’t help the coach work with an athlete and improve performance.’ says Peter Fricker, chief of science at AIS.

- A lot of their work comes down to measurement – everything from the exact angle of a swimmer’s dive to the second-by-second power output of a cyclist. This data is used to wring improvements out of athletes. The focus is on individuals, tweaking performances to squeeze an extra hundredth of a second here, an extra millimetre there. No gain is too slight to bother with. It’s the tiny, gradual improvements that add up to world-beating results. To demonstrate how the system works, Bruce Mason at AIS shows off the prototype of a 3D analysis tool for studying swimmers. A wire-frame model of a champion swimmer slices through the water, her arms moving in slow motion. Looking side-on, Mason measures the distance between strokes. From above, he analyses how her spine swivels. When fully developed, this system will enable him to build a biomechanical profile for coaches to use to help budding swimmers. Mason’s contribution to sport also includes the development of the SWAN (SWimming ANalysis) system now used in Australian national competitions. It collects images from digital cameras running at 50 frames a second and breaks down each part of a swimmer’s performance into factors that can be analysed individually – stroke length, stroke frequency, the average duration of each stroke, velocity, start, lap and finish times, and so on. At the end of each race, SWAN spits out data on each swimmer.

- ‘Take a look.’ says Mason, pulling out a sheet of data. He points out the data on the swimmers in second and third place, which shows that the one who finished third actually swam faster. So why did he finish 35 hundredths of a second down? ‘His turn times were 44 hundredths of a second behind the other guy.’ says Mason. ‘If he can improve on his turns, he can do much better.’ This is the kind of accuracy that AIS scientists’ research is bringing to a range of sports. With the Cooperative Research Centre for Micro Technology in Melbourne, they are developing unobtrusive sensors that will be embedded in an athlete’s clothes or running shoes to monitor heart rate, sweating, heat production or any other factor that might have an impact on an athlete’s ability to run. There’s more to it than simply measuring performance. Fricker gives the example of athletes who may be down with coughs and colds 11 or 12 times a year. After years of experimentation, AIS and the University of Newcastle in New South Wales developed a test that measures how much of the immune-system protein immunoglobulin A is present in athletes’ saliva. If IgA levels suddenly fall below a certain level, training is eased or dropped altogether. Soon, IgA levels start rising again, and the danger passes. Since the tests were introduced, AIS athletes in all sports have been remarkably successful at staying healthy

- Using data is a complex business. Well before a championship, sports scientists and coaches start to prepare the athlete by developing a ‘competition model’, based on what they expect will be the winning times. ‘You design the model to make that time.’ says Mason. ‘A start of this much, each free-swimming period has to be this fast, with a certain stroke frequency and stroke length, with turns done in these times’. All the training is then geared towards making the athlete hit those targets, both overall and for each segment of the race. Techniques like these have transformed Australia into arguably the world’s most successful sporting nation.

- Of course, there’s nothing to stop other countries copying – and many have tried. Some years ago, the AIS unveiled coolant-lined jackets for endurance athletes. At the Atlanta Olympic Games in 1996, these sliced as much as two per cent off cyclists’ and rowers times. Now everyone uses them. The same has happened to the altitude tent’, developed by AIS to replicate the effect of altitude training at sea level. But Australia’s success story is about more than easily copied technological fixes, and up to now no nation has replicated its all-encompassing system.

Questions 1-7

Reading Passage 1 has six paragraphs, A-F.

Which paragraph contains the following information?

Write the correct letter A-F in boxes 1-7 on your answer sheet.

NB You may use any letter more than once

- a reference to the exchange of expertise between different sports

- an explanation of how visual imaging is employed in investigations

- a reason for narrowing the scope of research activity

- how some AIS ideas have been reproduced

- how obstacles to optimum achievement can be investigated

- an overview of the funded support of athletes

- how performance requirements are calculated before an event

Questions 8-11

Classify the following techniques according to whether the writer states they –

- are currently exclusively used by Australians

- will be used in the future by Australians

- are currently used by both Australians and their rivals

Write the correct letter A, B, C or D in boxes 8-11 on your answer sheet.

- cameras

- sensors

- protein tests

- altitude tents

Questions 12 and 13

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS AND/OR A NUMBER from Reading Passage 1 for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 12 and 13 on your answer sheet.

- What is produced to help an athlete plan their performance in an event?

- By how much did some cyclists’ performance improve at the 1996 Olympic Games?

Reading Passage 2

Delivering The Goods

- The vast expansion in international trade owes much to a revolution in the business of moving freight. International trade is growing at a startling pace. While the global economy has been expanding at a bit over 3% a year, the volume of trade has been rising at a compound annual rate of about twice that.Foreign products, from meat to machinery, play a more important role in almost every economy in the world, and foreign markets now tempt businesses that never much worried about sales beyond their nation’s borders.

- What lies behind this explosion in international commerce? The general worldwide decline in trade barriers, such as customs duties and import quotas, is surely one explanation. The economic opening of countries that have traditionally been minor players is another. But one force behind the import-export boom has passed all but unnoticed: the rapidly falling cost of getting goods to market. But one force behind the import-export boom has passed all but unnoticed: the rapidly falling cost of getting goods to market. Theoretically, in the world of trade, shipping costs do not matter. Goods, once they have been made, are assumed to move instantly and at no cost from place to place. The real world, however, is full of frictions. Cheap labour may make Chinese clothing competitive in America, but if delays in shipment tie up working capital and cause winter coats to arrive in spring, trade may lose its advantages.

- At the turn of the 20th century, agriculture and manufacturing were the two most important sectors almost everywhere, accounting for about 70% of total output in Germany, Italy and France, and 40-50% in America, Britain and Japan. International commerce was therefore dominated by raw materials, such as wheat, wood and iron ore, or processed commodities, such as meat and steel. But these sorts of products are heavy and bulky and the cost of transporting them relatively high.

- Countries still trade disproportionately with their geographic neighbours. Over time, however, world output has shitted into goods whose worth is unrelated to their size and weight. Today, it is finished manufactured products that dominate the flow of trade, and, thanks to technological advances such as lightweight components, manufactured goods themselves have tended to become lighter and less bulky. As a result, less transportation is required for every dollar’s worth of imports or exports.

- To see how this influences trade, consider the business of making disk drives for computers. Most of the world’s disk-drive manufacturing is concentrated in South-east Asia. This is possible only because disk drives, while valuable, are small and light and so cost little to ship. Computer manufacturers in Japan or Texas will not face hugely bigger freight bills if they import drives from Singapore rather than purchasing them on the domestic market. Distance therefore poses no obstacle to the globalisation of the disk-drive industry.

- This is even more true of the fast-growing information industries. Films and compact discs cost little to transport, even by aeroplane. Computer software can be ‘exported’ without ever loading it onto a ship, simply by transmitting it over telephone lines from one country to another, so freight rates and cargo-handling schedules become insignificant factors in deciding where to make the product. Businesses can locate based on other considerations, such as the availability of labour, while worrying less about the cost of delivering their output.

- In many countries deregulation has helped to drive the process along. But, behind the scenes, a series of technological innovations known broadly as containerisation and intermodal transportation has led to swift productivity improvements in cargo-handling. Forty years ago, the process of exporting or importing involved a great many stages of handling, which risked portions of the shipment being damaged or stolen along the way. The invention of the container crane made it possible to load and unload containers without capsizing the ship and the adoption of standard container sizes allowed almost any box to be transported on any ship. By 1967, dual-purpose ships, carrying loose cargo in the hold* and containers on the deck, were giving way to all-container vessels that moved thousands of boxes at a time.

- The shipping container transformed ocean shipping into a highly efficient, intensely competitive business.But getting the cargo to and from the dock was a different story. National governments, by and large, kept firmer hand on truck and railroad tariffs than on charges for ocean freight. This started changing, however, in the mid-1970s, when America began to deregulate its transportation industry. First airlines, then road hauliers and railways, were freed from restrictions on what they could carry, where they could haul it and what price they could charge. Big productivity gains resulted. Between 1985 and 1996, for example, America’s freight railways dramatically reduced their employment, trackage, and their fleets of locomotives – while increasing the amount of cargo they hauled. Europe’s railways have also shown marked, albeit smaller, productivity improvements.

- In America the period of huge productivity gains in transportation may be almost over, but in most countries the process still has far to go. State ownership of railways and airlines, regulation of freight rates and toleration of anti-competitive practices, such as cargo-handling monopolies, all keep the cost of shipping unnecessarily high and deter international trade. Bringing these barriers down would help the world’s economies grow even closer.

Questions 14-17

Reading Passage 2 has six sections, A-I.

Write the correct letter A-I in boxes 14-17 on your answer sheet.

Which paragraph contains the following information?

- a suggestion for improving trade in the future

- the effects of the introduction of electronic delivery

- the similar cost involved in transporting a product from abroad or from a local supplier

- the weakening relationship between the value of goods and the cost of their delivery

Questions 18-22

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 2?

In boxes 18-22 on your answer sheet, write –

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

- International trade is increasing at a greater rate than the world economy.

- Cheap labour guarantees effective trade conditions.

- Japan imports more meat and steel than France.

- Most countries continue to prefer to trade with nearby nations.

- Small computer components are manufactured in Germany.

Questions 23-26

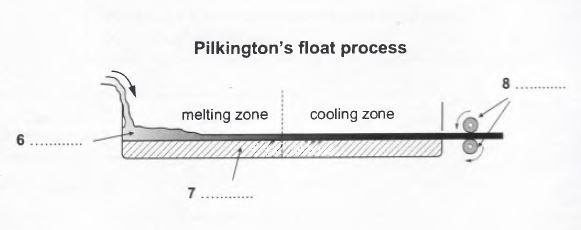

Complete the summary using the list of words, A-K, below.

Write the correct letter, A-K, in boxes 23-26 on your answer sheet.

THE TRANSPORT REVOLUTION

Modern cargo-handling methods have had a significant effect on (23)………………….. as the business of moving freight around the world becomes increasingly streamlined.Manufacturers of computers, for instance, are able to import (24)………………….. from overseas, rather than having to rely on a local supplier. The introduction of (25) ………………….. has meant that bulk cargo can be safely and efficiently moved over long distances. While international shipping is now efficient, there is still a need for governments to reduce (26)………………….. in order to free up the domestic cargo sector.

| A tariffs | B components | C container ships |

| D output | E employees | F insurance costs |

| G trade | H freightI fares | J software |

| K international standards |

Reading Passage 3

Climate change and the Inuit

- Unusual incidents are being reported across the Arctic. Inuit families going off on snowmobiles to prepare their summer hunting camps have found themselves cut off from home by a sea of mud, following early thaws. There are reports of igloos losing their insulating properties as the snow drips and refreezes, of lakes draining into the sea as permafrost melts, and sea ice breaking up earlier than usual, carrying seals beyond the reach of hunters. Climate change may still be a rather abstract idea to most of us, but in the Arctic, it is already having dramatic effects – if summertime ice continues to shrink at its present rate, the Arctic Ocean could soon become virtually ice-free in summer. The knock-on effects are likely to include more warming, cloudier skies, increased precipitation and higher sea levels. Scientists are increasingly keen to find out what’s going on because they consider the Arctic the ‘canary in the mine’ for global warming – a warning of what’s in store for the rest of the world.

- For the Inuit the problem is urgent. They live in precarious balance with one of the toughest environments on earth. Climate change, whatever its causes, is a direct threat to their way of life. Nobody knows the Arctic as well as the locals, which is why they are not content simply to stand back and let outside experts tell them what’s happening. In Canada, where the Inuit people are jealously guarding their hard-won autonomy in the country’s newest territory – Nunavut, they believe their best hope of survival in this changing environment lies in combining their ancestral knowledge with the best of modern science. This is a challenge in itself.

- The Canadian Arctic is a vast, treeless polar desert that’s covered with snow for most of the year. Venture into this terrain and you get some idea of the hardships facing anyone who calls this home. Farming is out of the question and nature offers meagre pickings. Humans first settled in the Arctic a mere 4,500 years ago, surviving by exploiting sea mammals and fish. The environment tested them to the limits: sometimes the colonists were successful, sometimes they failed and vanished. But around a thousand years ago, one group emerged that was uniquely well adapted to cope with the Arctic environment. These Thule people moved in from Alaska, bringing kayaks, sleds, dogs, pottery and iron tools. They are the ancestors of today’s Inuit people.

- Life for the descendants of the Thule people is still harsh. Nunavut is 1.9 million square kilometres of rock and ice, and a handful of islands around the North Pole. It’s currently home to 2,500 people, all but a handful of them indigenous Inuit. Over the past 40 years, most have abandoned their nomadic ways and settled in the territory’s 28 isolated communities, but they still rely heavily on nature to provide food and clothing. Provisions available in local shops have to be flown into Nunavut on one of the most costly air networks in the world, or brought by supply ship during the few ice-free weeks of summer. It would cost a family around £7,000 a year to replace meat they obtained themselves through hunting with imported meat. Economic opportunities are scarce, and for many people state benefits are their only income.

- While the Inuit may not actually starve if hunting and trapping are curtailed by climate change, there has certainly been an impact on people’s health. Obesity, heart disease and diabetes are beginning to appear in a people for whom these have never before been problems. There has been a crisis of identity as the traditional skills of hunting, trapping and preparing skins have begun to disappear. In Nunavut’s ‘igloo and email’ society, where adults who were born in igloos have children who may never have been out on the land, there’s a high incidence of depression.

- With so much at stake, the Inuit are determined to play a key role in teasing out the mysteries of climate change in the Arctic. Having survived there for centuries, they believe their wealth of traditional knowledge is vital to the task. And Western scientists are starting to draw on this wisdom, increasingly referred to as ‘Inuit Qaujimajatugangit’, or IQ. ‘In the early days, scientists ignored us when they came up here to study anything. They just figured these people don’t know very much so we won’t ask them,’ says John Amagoalik, an Inuit leader and politician. ‘But in recent years IQ has had much more credibility and weight.’ In fact it is now a requirement for anyone hoping to get permission to do research that they consult the communities, who are helping to set the research agenda to reflect their most important concerns. They can turn down applications from scientists they believe will work against their interests or research projects that will impinge too much on their daily lives and traditional activities.

- Some scientists doubt the value of traditional knowledge because the occupation of the Arctic doesn’t go back far enough. Others, however, point out that the first weather stations in the far north date back just 50 years. There are still huge gaps in our environmental knowledge, and despite the scientific onslaught, many predictions are no more than best guesses. IQ could help to bridge the gap and resolve the tremendous uncertainty about how much of what we’re seeing is natural capriciousness and how much is the consequence of human activity.

Questions 27-32

Reading Passage has seven paragraphs, A-G.

Choose the correct heading for paragraphs B-G from the list of headings below.

Write the correct number, i-ix, in boxes 1-6 on your answer sheet.

List of Headings

- The reaction of the limit community to climate change

- Understanding of climate change remains limited

- Alternative sources of essential supplies

- Respect for limit opinion grows

- A healthier choice of food

- A difficult landscape

- Negative effects on well-being

- Alarm caused by unprecedented events in the Arctic

- The benefits of an easier existence

Example Answer

Paragraph A (answer) viii

- Paragraph B

- Paragraph C

- Paragraph D

- Paragraph E

- Paragraph F

- Paragraph G

Questions 33-40

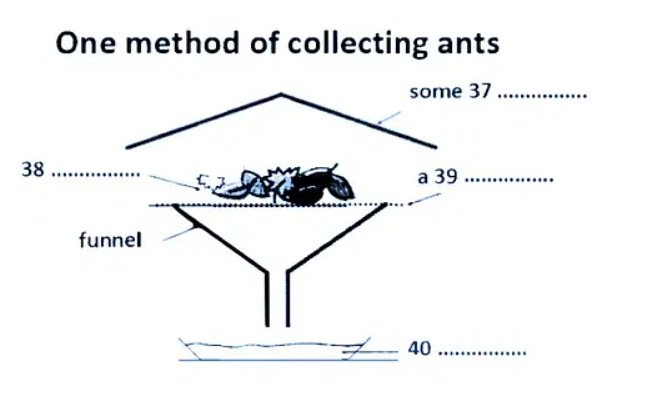

Complete the summary of paragraphs C and D below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from paragraphs C and D for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 33-40 on your answer sheet.

If you visit the Canadian Arctic, you immediately appreciate the problems faced by people for whom this is home. It would clearly be impossible for the people to engage in (33) ……………….. as a means of supporting themselves. For thousands of years they have had to rely on catching (34)……………….. and (35)……………….. as a means of sustenance. The harsh surroundings saw many who tried to settle there pushed to their limits, although some were successful. The (36) ……………….. people were an example of the latter and for them the environment did not prove unmanageable. For the present inhabitants, life continues to be a struggle. The territory of Nunavut consists of little more than ice, rock and a few (37) ……………….. . In recent years, many of them have been obliged to give up their (38) ……………….. lifestyle, but they continue to depend mainly on (39) ……………….. their food and clothes. (40) ……………….. produce is particularly expensive.

Reading Passage 1 Australia’s Sporting Success Answers

- B

- C

- B

- F

- D

- A

- E

- A

- B

- A

- C

- competition model

- 2%

Reading Passage 2 Delivering The Goods Answers

- I

- F

- E

- D

- true

- false

- not given

- true

- not given

- trade

- components

- container ships

- tariffs

Reading Passage 3 Climate change and the Inuit Answers

- i

- vi

- iii

- vii

- iv

- ii

- farming

- sea mammals

- fish

- thule

- islands

- nomadic

- nature

- imported