Reading Passage 1

The power of the big screen

- The Lumière Brothers opened their Cinematographe, at 14 Boulevard des Capucines in Paris, to 100 paying customers over 100 years ago, on December 8, 1985. Before the eyes of the stunned, thrilled audience, photographs came to life and moved across a flat screen.

- So ordinary and routine has this become to us that it takes a determined leap of imagination to grasp the impact of those first moving images. But it is worth trying, for to understand the initial shock of those images is to understand the extraordinary power and magic of cinema, the unique, hypnotic quality that has made films the most dynamic, effective art form of the 20th century.

- One of the Lumière Borthers’ earliest films was a 30-second piece which showed a section of a railway platform flooded with sunshine. A train appears and heads straight for the camera. And that is all that happens. Yet the Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky, one of the greatest of all film artists, described the film as a ‘work of genius’. ‘As the train approached,’ wrote Tarkovsky, ’panic started in the theatre: people jumped and ran away. That was the moment when cinema was born. The frightened audience could not accept that they were watching a mere picture. Pictures were still, only reality moved; this must, therefore, be reality. In their confusion, they feared that a real train was about to crush them.’

- Early cinema audiences often experienced the same confusion. In time, the idea of films became familiar, the magic was accepted- but it never stopped being magic. Film has never lost its unique power to embrace its audience and transport them to a different world. For Tarkovsky, the key to that magic dynamic image of the real flow of events, a still picture could only imply the existence of time, while time in a novel passed at the whim of the reader, but in cinema, the real, objective flow of time was captured.

- One effect of this realism was to educate the world about itself. For cinema makes the world smaller. Long before people travelled to America or anywhere else, they knew what other places looked like; they knew how other people worked and lived. Overwhelmingly, the lives recorded at least in film fiction- have been American. From the earliest days of the industry, Hollywood has dominated the world film market. American imagery-the cars, the cities, the cowboys became the primary imagery of film. Film carried American life and values around the globe.

- And, thanks to film, future generations will know the 20-th century more intimately than any other period. We can only imagine what life was like in the 14th century or in classical Rome. But the life of the modern world has been recorded on film in massive encyclopaedic detail. We shall be known better than any preceding generations.

- The ‘star’ was another natural consequence of cinema. The cinema star was effectively born in 1910. Film personalities have such an immediate presence that inevitably, they become super-real. Because we watch them so closely and because everybody in the world seems to know who they are, they appear more real to us than we do ourselves. The star as magnified human self is one of cinema’s most strange and enduring legacies.

- Cinema has also given a new lease of life to the idea of the story. When the Lumiere Brothers and other pioneers began showing off this new invention, it was by no means obvious how it would be used. All that mattered at first was the wonder of movement. Indeed, some said that, once this novelty had worn off, cinema would fade away. It was no more than a passing gimmick, a fairground attraction.

- Cinema might, for example, have become primarily a documentary form. Or it might have developed like television -as a strange noisy transfer of music, information and narrative. But what happened was that it became, overwhelmingly, a medium for telling stories. Originally these were conceived as short stories- early producers doubted the ability of audiences to concentrate for more than the length of a reel. Then, in 1912, an Italian 2-hour film was hugely successful, and Hollywood settled upon the novel-length narrative that remains the dominant cinematic convention of today.

- And it has all happened so quickly. Almost unbelievably, it is a mere 100 years since that train arrived and the audience screamed and fled, convinced by the dangerous reality of what they saw, and, perhaps, suddenly aware that the world could never be the same again -that, maybe, it could be better, brighter, more astonishing, more real than reality.

Questions 1-5

Reading Passage 1has ten paragraphs, A-J.

Which paragraph contains the following information?

Write the correct letter, A-J. in boxes 1-5 on your answer sheet.

- the location of the first cinema

- how cinema came to focus on stories

- the speed with which cinema has changed

- how cinema teaches us about other cultures

- the attraction of actors in films

Questions 6-9

Do the following statements agree with the views of the writer in Reading Passage 1?

In boxes 6-9 on your answer sheet, write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the views of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the views of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

- It is important to understand how the first audiences reacted to the cinema.

- The Lumiere Brothers’ film about the train was one of the greatest films ever made.

- Cinema presents a biased view of other countries.

- Storylines were important in very early cinema.

Questions 10-13

Choose the correct letter. A, B, C or D.

Write the correct letter in boxes 10-13 on your answer sheet.

- The writer refers to the film of the train in order to demonstrate

- the simplicity of early films.

- the impact of early films.

- how short early films were.

- how imaginative early films were.

- In Tarkovsky’s opinion, the attraction of the cinema is that it

- aims to impress its audience.

- tells stories better through books.

- illustrates the passing of time.

- describes familiar events.

- When cinema first began, people thought that

- it would always tell stories.

- it should be used in fairgrounds.

- US audiences were unappreciative.

- its future was uncertain.

- What is the best title for this passage?

- The rise of the cinema star

- Cinema and novels compared

- The domination of Hollywood

- The power of the big screen

Reading Passage 2

Motivating Employees under Adverse Condition

THE CHALLENGE

It is a great deal easier to motivate employees in a growing organisation than a declining one. When organisations are expanding and adding personnel, promotional opportunities, pay rises, and the excitement of being associated with a dynamic organisation create feelings of optimism. Management is able to use the growth to entice and encourage employees. When an organisation is shrinking, the best and most mobile workers are prone to leave voluntarily. Unfortunately, they are the ones the organisation can least afford to lose- those with the highest skills and experience. The minor employees remain because their job options are limited.

Morale also suffers during decline. People fear they may be the next to be made redundant. Productivity often suffers, as employees spend their time sharing rumours and providing one another with moral support rather than focusing on their jobs. For those whose jobs are secure, pay increases are rarely possible. Pay cuts, unheard of during times of growth, may even be imposed. The challenge to management is how to motivate employees under such retrenchment conditions. The ways of meeting this challenge can be broadly divided into six Key Points, which are outlined below.

KEY POINT ONE

There is an abundance of evidence to support the motivational benefits that result from carefully matching people to jobs. For example, if the job is running a small business or an autonomous unit within a larger business, high achievers should be sought. However, if the job to be filled is a managerial post in a large bureaucratic organisation, a candidate who has a high need for power and a low need for affiliation should be selected. Accordingly, high achievers should not be put into jobs that are inconsistent with their needs. High achievers will do best when the job provides moderately challenging goals and where there is independence and feedback. However, it should be remembered that not everybody is motivated by jobs that are high in independence, variety and responsibility.

KEY POINT TWO

The literature on goal-setting theory suggests that managers should ensure that all employees have specific goals and receive comments on how well they are doing in those goals. For those with high achievement needs, typically a minority in any organisation, the existence of external goals is less important because high achievers are already internally motivated. The next factor to be determined is whether the goals should be assigned by a manager or collectively set in conjunction with the employees. The answer to that depends on perceptions the culture, however, goals should be assigned. If participation and the culture are incongruous, employees are likely to perceive the participation process as manipulative and be negatively affected by it.

KEY POINT THREE

Regardless of whether goals are achievable or well within management’s perceptions of the employee’s ability, if employees see them as unachievable they will reduce their effort. Managers must be sure, therefore, that employees feel confident that their efforts can lead to performance goals. For managers, this means that employees must have the capability of doing the job and must regard the appraisal process as valid.

KEY POINT FOUR

Since employees have different needs, what acts as a reinforcement for one may not for another. Managers could use their knowledge of each employee to personalise the rewards over which they have control. Some of the more obvious rewards that managers allocate include pay, promotions, autonomy, job scope and depth, and the opportunity to participate in goal-setting and decision-making.

KEY POINT FIVE

Managers need to make rewards contingent on performance. To reward factors other than performance will only reinforce those other factors. Key rewards such as pay increases and promotions or advancements should be allocated for the attainment of the employee’s specific goals. Consistent with maximising the impact of rewards, managers should look for ways to increase their visibility. Eliminating the secrecy surrounding pay by openly communicating everyone’s remuneration, publicising performance bonuses and allocating annual salary increases in a lump sum rather than spreading them out over an entire year are examples of actions that will make rewards more visible and potentially more motivating.

KEY POINT SIX

The way rewards were distributed should be transparent so that employees perceive that rewards or outcomes are equitable and equal to the inputs given. On a simplistic level, experience, abilities, effort and other obvious inputs should explain differences in pay, responsibility and other obvious outcomes. The problem, however, is complicated by the existence of dozens of inputs and outcomes and by the fact that employee groups place different degrees of importance on them. For instance, a study comparing clerical and production workers identified nearly twenty inputs and outcomes. The clerical workers considered factors such as quality of work performed and job knowledge near the top of their list, but these were at the bottom of the production workers’ list. Similarly, production workers thought that the most important inputs were intelligence and personal involvement with task accomplishment, two factors that were quite low in the importance ratings of the clerks. There were also important, though less dramatic, differences on the outcome side. For example, production workers rated advancement very highly, whereas clerical workers rated advancement in the lower third of their list. Such findings suggest that one person’s equity is another’s inequity, so an ideal should probably weigh different inputs and outcomes according to employee group.

Questions 14-18

Reading Passage 2 contains six Key Points.

Choose the correct heading for Key Points TWO to SIX from the list of headings below.

Write the correct number, i-viii, in boxes 14-18 on your answer sheet.

List of Headings

- Ensure the reward system is fair

- Match rewards to individuals

- Ensure targets are realistic

- Link rewards to achievementv Encourage managers to take more responsibility

- Recognise changes in employees’ performance over time

- Establish targets and give feedback

- Ensure employees are suited to their jobs

Example

Key Point One (answer) viii

- Key Point Two

- Key Point Three

- Key Point Four

- Key Point Five

- Key Point Six

Questions 19-24

Do the following statements agree with the views of the writer in Reading Passage 2?

In boxes 19-24 on your answer sheet, write:

- YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

- A shrinking organisation lends to lose its less skilled employees rather than its more skilled employees.

- It is easier to manage a small business than a large business.

- High achievers are well suited to team work.

- Some employees can feel manipulated when asked to participate in goal-setting.

- The staff appraisal process should be designed by employees.

- Employees’ earnings should be disclosed to everyone within the organisation.

Questions 25-27

Look at the follow groups of worker (Question25-27) and the list of descriptions below.

Match each group with the correct description, A-E.

Write the correct letter, A-E, in boxes 25-27 on your answer sheet.

- high achievers

- clerical workers

- production workers

List of Descriptions

- They judge promotion to be important

- They have less need of external goats

- They think that the quality of their work is important

- They resist goals which are imposed

- They have limited job options

Reading Passage 3

The Search for the Anti-aging Pill

In government laboratories and elsewhere, scientists are seeking a drug able to prolong life and youthful vigor. Studies of caloric restriction are showing the way.

As researchers on aging noted recently, no treatment on the market today has been proved to slow human aging- the build-up of molecular and cellular damage that increases vulnerability to infirmity as we grow older. But one intervention, consumption of a low-calorie* yet nutritionally balanced diet, works incredibly well in a broad range of animals, increasing longevity and prolonging good health. Those findings suggest that caloric restriction could delay aging and increase longevity in humans, too.

Unfortunately, for maximum benefit, people would probably have to reduce their caloric intake by roughly thirty percent, equivalent to dropping from 2,500 calories a day to 1, 750. Few mortals could stick to that harsh regimen, especially for years on end. But what if someone could create a pill that mimicked the physiological effects of eating less without actually forcing people to eat less? Could such a ‘caloric-restriction mimetic’, as we call it, enable people to stay healthy longer, postponing age-related disorders (such as diabetes, arteriosclerosis, heart disease and cancer) until very late in life? Scientists first posed this question in the mid-1990s, after researchers came upon a chemical agent that in rodents seemed to reproduce many of caloric restriction’s benefits. No compound that would safely achieve the same feat in people has been found yet, but the search has been informative and has fanned the hope that caloric-restriction (CR) mimetics can indeed be developed eventually.

The benefits of caloric restriction

The hunt for CR mimetics grew out of a desire to better understand caloric restriction’s many effects on the body. Scientists first recognized the value of the practice more than 60 years ago, when they found that rats fed a low-calorie diet lived longer on average than free-feeding rats and also had a reduced incidence of conditions that become increasingly common in old age. What is more, some of the treated animals survived longer than the oldest-living animals in the control group, which means that the maximum lifespan (the oldest attainable age), not merely the normal lifespan, increased. Various interventions, such as infection-fighting drugs, can increase a population’s average survival time, but only approaches that slow the body’s rate of aging will increase the maximum lifespan.

The rat findings have been replicated many times and extended to creatures ranging from yeast to fruit flies, worms, fish, spiders, mice and hamsters. Until fairly recently, the studies were limited short-lived creatures genetically distant from humans. But caloric-restriction projects underway in two species more closely related to humans- rhesus and squirrel monkeys- have scientists optimistic that CR mimetics could help people.

calorie: a measure of the energy value of food.

The monkey projects demonstrate that compared with control animals that eat normally caloric-restricted monkeys have lower body temperatures and levels of the pancreatic hormone insulin, and they retain more youthful levels of certain hormones that tend to fall with age.

The caloric-restricted animals also look better on indicators of risk for age-related diseases. For example, they have lower blood pressure and triglyceride levels(signifying a decreased likelihood of heart disease) and they have more normal blood glucose levels( pointing to a reduced risk for diabetes, which is marked by unusually high blood glucose levels). Further, it has recently been shown that rhesus monkeys kept on caloric-restricted diets for an extended time( nearly 15 years) have less chronic disease. They and the other monkeys must be followed still longer, however, to know whether low-calorie intake can increase both average and maximum lifespans in monkeys. Unlike the multitude of elixirs being touted as the latest anti-aging cure, CR mimetics would alter fundamental processes that underlie aging. We aim to develop compounds that fool cells into activating maintenance and repair.

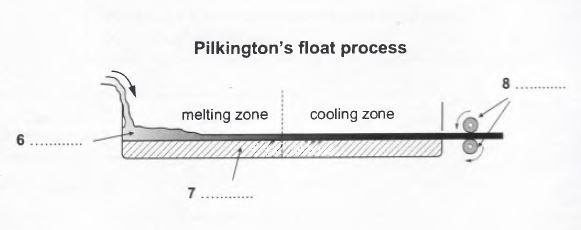

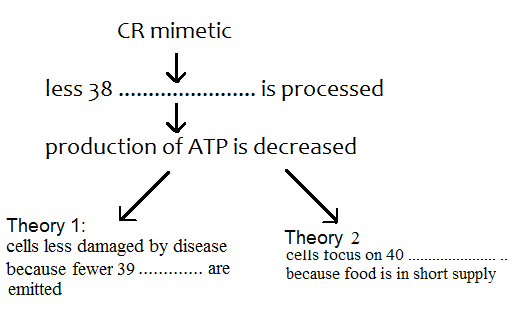

How a prototype caloric-restriction mimetic works

The best-studied candidate for a caloric-restriction mimetic, 2DG (2-deoxy-D-glucose), works by interfering with the way cells process glucose, it has proved toxic at some doses in animals and so cannot be used in humans. But it has demonstrated that chemicals can replicate the effects of caloric restriction; the trick is finding the right one.

Cells use the glucose from food to generate ATP (adenosine triphosphate), the molecule that powers many activities in the body. By limiting food intake, caloric restriction minimizes the amount of glucose entering cells and decreases ATP generation. When 2DG is administered to animals that eat normally, glucose reaches cells in abundance but the drug prevents most of it from being processed and thus reduces ATP synthesis. Researchers have proposed several explanations for why interruption of glucose processing and ATP production might retard aging. One possibility relates to the ATP-making machinery’s emission of free radicals, which are thought to contribute to aging and such age-related diseases as cancer by damaging cells. Reduced operation of the machinery should limit their production and thereby constrain the damage. Another hypothesis suggests that decreased processing of glucose could indicate to cells that food is scarce( even if it isn’t) and induce them to shift into an anti-aging mode that emphasizes preservation of the organism over such ‘luxuries’ as growth and reproduction.

Questions 28-32

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Reading Passage 3?

Inboxes 28-32 on your answer sheet, write

- YES if the statement t agrees with the claims of the writer

- NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

- NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

- Studies show drugs available today can delay the process of growing old.

- There is scientific evidence that eating fewer calories may extend human life.

- Not many people are likely to find a caloric-restricted diet attractive.

- Diet-related diseases are common in older people.

- In experiments, rats who ate what they wanted to lead shorter lives than rats on a low-calorie diet.

Questions 33-37

Classify the following descriptions as relating to

- caloric-restricted mimetic

- control monkeys

- neither caloric-restricted monkeys nor control monkeys

Write the correct letter, A, B or C, in boxes 33-37 on your answer sheet.

- Monkeys were less likely to become diabetic.

- Monkeys experienced more chronic disease.

- Monkeys have been shown to experience a longer than average life span.

- Monkeys enjoyed a reduced chance of heart disease.

- Monkeys produced greater quantities of insulin.

Questions 38-40

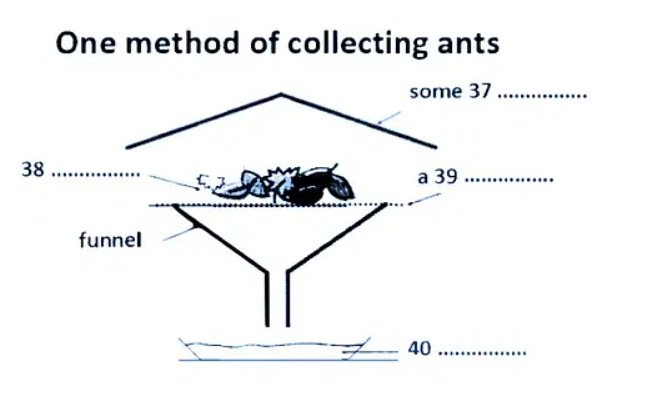

Complete the flowchart below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 38-40 on your answer sheet.

How a caloric-restriction mimetic works

Reading Passage 1 The Lumiere Brothers opened their Cinematographe Answers

- A

- I

- J

- E

- G

- yes

- not given

- not given

- no

- B

- C

- D

- D

Reading Passage 2 Motivating Employees under Adverse Condition Answers

- VII

- III

- II

- IV

- I

- no

- not given

- no

- yes

- not given

- yes

- B

- C

- A

Reading Passage 3 The Search for the Anti-aging Pill Answers

- no

- yes

- yes

- not given

- yes

- A

- B

- C

- A

- B

- glucose

- free radicals

- preservation